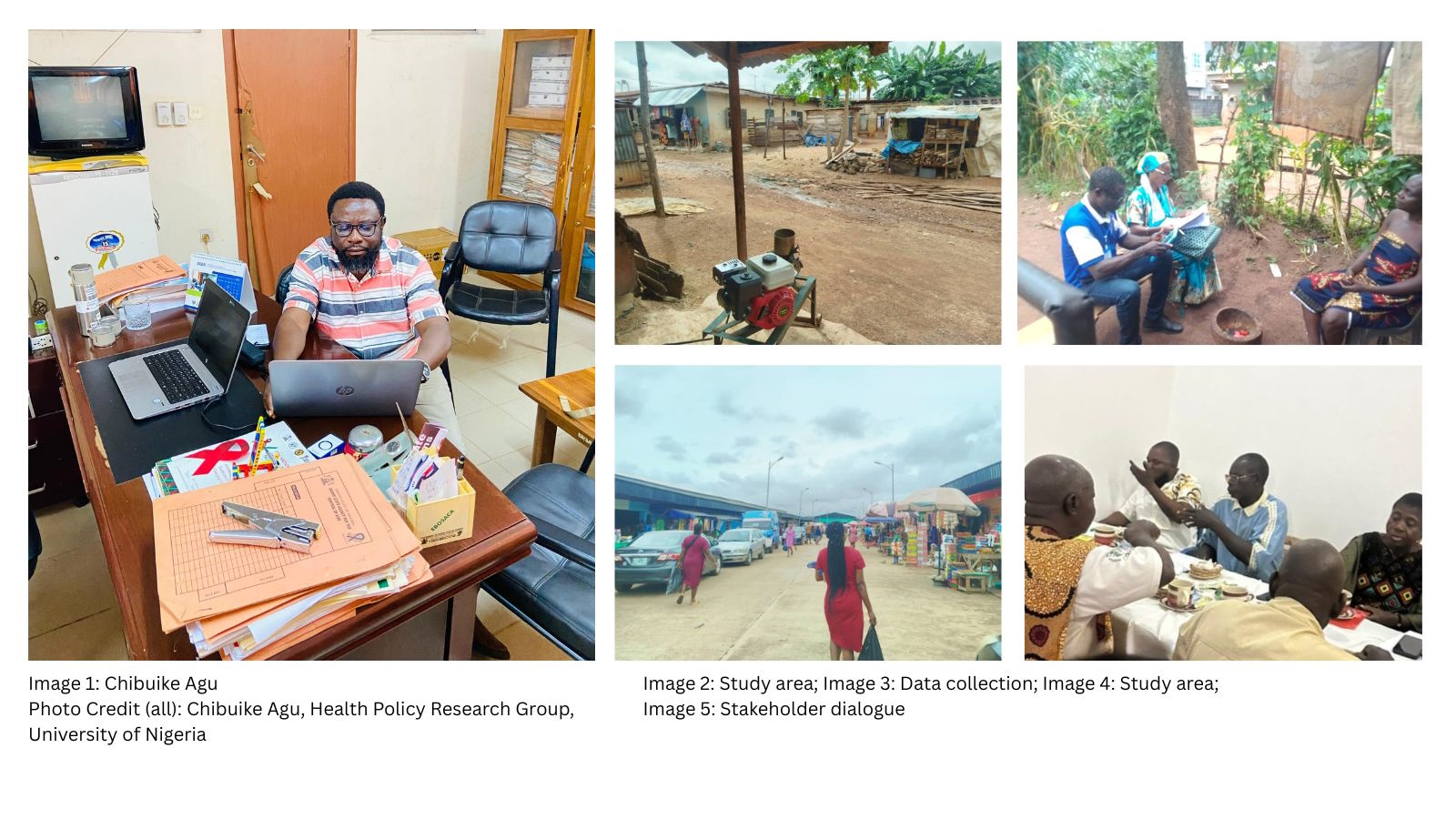

Innovation Fund Holder Interview in 10 Series: Chibuike Agu

Chibuike Agu, at the Health Policy Research Group, University of Nigeria, leads a CHORUS Innovation Fund project on the ‘Quality and Patterns of Antimicrobial Dispensing and Consumption in Urban Slums in Ebonyi, Nigeria’.

We asked Chibuike about his inspirations, learnings and highlights of his project. Chibuike shares some interesting observations, and the importance of working with the informal health sector if we are to make progress in the fight against antimicrobial resistance.

1. Can you explain your research in 100 words

Our research looks at how people in urban slums of Ebonyi State, Nigeria use antimicrobial agents, such as antimalarials, antibiotics, antifungals, etc., and how patent medicine vendors (PMVs), dispense them. We’re exploring how often these medicines are sold to their clients, the types most commonly sold, and how people in these communities take them. We also want to understand how factors like gender, social beliefs, and norms shape these practices. By uncovering these patterns, our goal is to provide evidence that can guide better policies and regulations to ensure antimicrobials are used wisely and help fight the growing problem of antimicrobial resistance.

2. What makes your research project ‘innovative’?

What makes our research innovative is our adaptation of the WHO/INRUD prescribing indicators form, usually applied in formal healthcare settings, to observe how PMVs dispensed antimicrobials. This creative approach provides globally comparable data from an informal context and generates information that can guide policies to improve antimicrobial use.

3. In your view, what is the most important aspect of your research project?

The most important aspect of our project is that it goes beyond just how antimicrobials are sold and used, but it looks into the social realities behind those behaviours. We’re exploring how gender, beliefs, and community norms influence behaviour, while also examining dispensing and consumption patterns in urban slums.

4. What drew you to this area of research?

I was drawn to this area of research following my observation of the over-reliance of residents of urban slums on PMVs, who sell all kinds of medicines, including antibiotics, antiviral, antifungal agents without restriction. Many even administer injections, and intravenous antibiotics, that are supposed to be given only by doctors in tertiary care settings in our country. Aware that antimicrobial resistance is a growing public health threat, I was eager to dig into the activities of these category of providers, the use of antimicrobials in the communities, as well as the social drivers of these behaviours.

5. What has surprised you most during your project?

What surprised me most during the project was that antibiotics are not just being used for all manner of medical conditions, but also for non-medical reasons. For example, many people talked about using them to ‘flush’ or ‘cleanse’ their system every now and then, almost like a routine tonic. Even more striking, some women reported using antibiotics as abortion agents. It really showed me that antibiotics in these communities have become multipurpose tools embedded in their beliefs, and daily survival strategies.

6. What has been your biggest learning?

My biggest learning from the project is the practice people call ‘washing and setting.’ It involves the use of antibiotics to ‘cleanse or flush the system’ once in a while, especially after sex. I was struck by how common this was for both men and women, though it seemed more frequent among men. It really showed me that antibiotics aren’t just seen as medicine, but also as part of cultural health practices, which makes the issue of resistance even more compounded.

7. What would you like other researchers to learn from your project?

First of all, the importance of building and nurturing relationships with stakeholders. In our study, attending to clients and supporting the research process placed an extra burden on the PMVs. What really helped us, especially during the second phase of the project, was the strong relationships we had already established with both the PMVs themselves and community leaders. These relationships, including ties with the PMV association, proved invaluable. Another key lesson is that antimicrobial use, particularly antibiotics is deeply tied to social norms and even survival strategies within the community.

8. What more would you like to do with your project or research area – if funding wasn’t a constraint?

I would like to take this project beyond documenting dispensing and consumption and move into actually testing solutions in real-world settings. For example, we could pilot co-created, harm-reduction, community-embedded interventions with PMVs and community members, while ensuring that clients with serious conditions are linked to formal health facilities through a guided referral process. This would also give us the chance to tackle gender and other social norms that drive some of these practices and fuel antimicrobial resistance.

9. What do you wish you had known at the start of the project, that you know now?

One thing I wish I had known is the dilemma that PMVs face about dispensing antimicrobials. Initially, I thought inappropriate sales were mainly due to lack of knowledge or weak regulation. But what became clear is the dilemma they face every day: if they refuse to sell an antibiotic when a client insists, they risk losing that customer entirely. And with that loss goes the income they would have made, which for many is crucial to their survival. On the other hand, if they do sell, they know it might not be the right thing medically. This constant tension between maintaining livelihood and adhering to proper practice is, sometimes, at the heart of their behaviour.

10. Is there anything else you would like to share about your project, or the process?

If the fight against antimicrobial resistance is to make real progress, it has to prioritize the informal sector, especially in urban slums. That’s where antibiotics are not only used for virtually every health condition, but also for non-medical reasons, such as, ‘flushing’ the system or even as abortion agents. Unless we address these realities at the community level, efforts to control resistance will remain incomplete.